The Spectrum of Dissociation

What is dissociation? Most of us have daydreamed, right? I can think back to many times in K-12 when a teacher scolded me for gazing out the window, and I certainly wasn’t the only one! Some people are more “head in the clouds” than others, but most of us at one point or another “zone out” when a work meeting is droning on or when there’s a stressful situation that’s got you feeling overwhelmed. All of these examples are mild, everyday forms of dissociation.

Ever heard of ‘highway hypnosis’? This is another form of dissociation, when we get home from a drive and realize we forgot the actual journey back, yet somehow still managed to get home safely. This can be a scary experience, but you made it–and your brain helped you do it. Often, a mild dissociative experience is not harmful, but with increase of severity and occurrences, it can interfere with daily life.

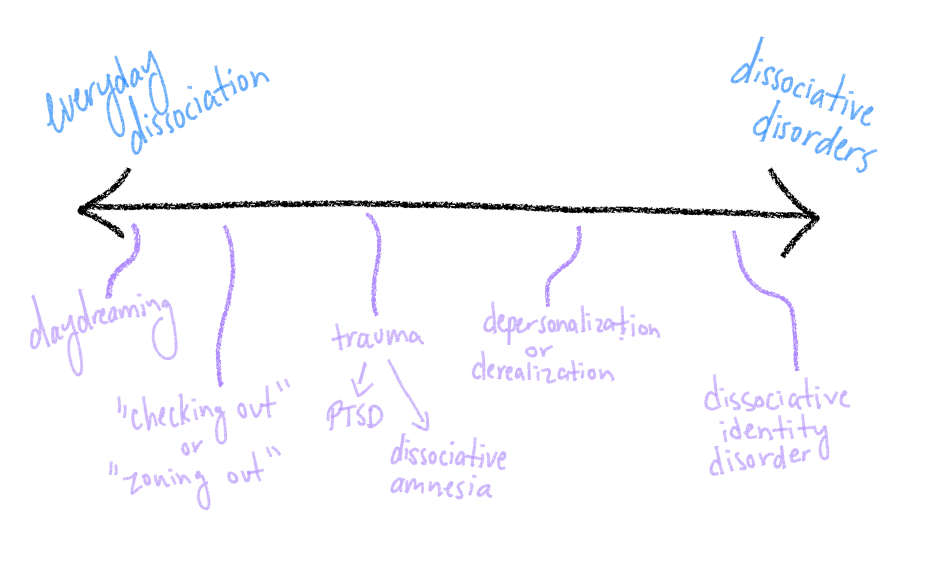

Dissociation ranges on a spectrum of severity and experience, but is often described as a disconnectedness from your present state. This means a person experiences a disconnectedness from their thoughts, memories, feelings, actions, surroundings, and sometimes from themselves and their identity (APA, 2013).

Along the spectrum of dissociation, experiences may include:

- “Spacing out” or getting caught staring at a specific point for a long time or struggling to focus your vision

- Forgetting things that should be easily accessible in your memory

- Derealization- where the world around you doesn’t feel or look real

- Depersonalization - where you observe your body as if it were someone else’s

- Fragmentation of identity

The disconnectedness from your conscious awareness can be disconcerting when there are gaps in your memory or when you become unaware of your thoughts or surroundings, but its a skill your brain has grown to actually help you in some way or another.

Anyone can “zone-out” at work or in the car, but for some, this skill has been honed in response to various traumas from childhood meant to protect oneself. In a way, this is how your brain acts in self-preservation when situations are too painful or damaging to stay aware. In a traumatic situation where a child may fear for their safety or life, this “dissociative switch” can be turned on to allow the person to disconnect from themselves until the threat is resolved, or at least manageable.

If the threat continues, this can result in the brain developing conditions later on such as depersonalization/derealization disorder, dissociative amnesia, or dissociative identity disorder. All of these could occur from chronic early childhood traumas like physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, being subjected to a highly unpredictable and frightening home environment, or the stress of war or natural disasters.

Depersonalization/derealization disorder

The depersonalization part of this disorder is characterized by experiencing a distorted sense of time, absence of self, and emotional or physical numbing. The derealization side is characterized by things not seeming real, as if you’re looking through a screen, or seeing things as dreamlike or foggy.

Dissociative amnesia

Dissociative amnesia refers to when a person experiences a loss of memory regarding personal information due to overwhelming stress, by traumatic events, or there may be a genetic predisposition. This memory loss could be only specific events or the person’s history or identity, but in all cases it is more severe than typical “forgetfulness.” Although rare, there have been cases where a person goes into a dissociative fugue state, forgetting most of the one’s identity and history, and subsequently finding themselves adopting a totally different identity.

Dissociative identity disorder

Dissociative identity disorder relates to when one’s identity becomes fragmented, creating a system that can manage the trauma in order to survive the hostile environment. Each identity within the system may have their own “role” in protecting the system. These identities may or may not be aware of one another, so it can be a surprise to some when a diagnosis is made. Treatment can help the system to learn to coexist in healthier manners that are less harmful to the individual identities.

Treatment can help you to understand what you are experiencing, discover sources of triggers, process through any trauma, and learn helpful ways to ground yourself to the present moment. This treatment can help reduce instances of disturbances, improve daily functioning, and feel more confident in your ability to be present throughout the day.

If you or anyone you know is experiencing difficulties with dissociation, reach out to your therapist and share your concerns with them. If you don’t have a therapist you can start that journey by looking in your local area on PsychologyToday or reach out to Caladrius Therapy for an appointment with one of our skilled therapists.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.